| |

Murad III 1546-1595 1574-1595 |

Murad III (W)

Murad III (1546-1595) (1574-1595) (W)

Family

- Consorts

Murad's named consorts were:

Sons

Murad had twenty-two sons:

- Sultan Mehmed III (26 May 1566 – 22 December 1603, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Mehmed III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque, Constantinople), became the next sultan;

- Şehzade Mahmud (1568, Manisa Palace, Manisa – 1581, Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Mustafa (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Osman (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Bayezid (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Selim (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Cihangir (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Abdullah (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Abdurrahman (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Hasan (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ahmed (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Yakub (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Alemşah (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Yusuf (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Hüseyin (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Korkud (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ali (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ishak (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ömer (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Alaeddin (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Davud (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Suleiman (murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque):

- Sehzade Yahya (Executed by the orders of late Sultan Ahmed I 1621)

Daughters

Murad had twenty-eight daughters, of whom sixteen died of plague in 1597. The rest, who were married, included the following:

- Hüma Sultan, married firstly to Damad Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha (died 1580), married secondly to Damad Nişar Mustafazade Mehmed Pasha (died 1586);

- Ayşe Sultan (died 15 May 1605, buried in Mehmed III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), daughter with Safiye, married firstly on 20 May 1586, to Damat Ibrahim Pasha, married secondly on 5 April 1602, to Damad Yemişçi Hasan Pasha, married thirdly on 29 June 1604, to Damad Güzelce Mahmud Pasha;

- Fatma Sultan (died 1620 buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), daughter with Safiye, married firstly on 6 December 1593, to Damad Halil Pasha, married secondly December 1604, to Damad Hızır Pasha;

- Rukiye Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), daughter with Şemsiruhsar Hatun, married to Damad Nakkaş Hasan Pasha;

- Mihriban Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), married in 1613 to Damad Kapıcıbaşı Topal Mehmed Agha;

- Fahri Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), married to Damad Sofu Bayram Pasha, sometime Governor of Bosnia;

- Mihrimah Sultan, married firstly in 1613 to Damad Ahmed Pasha, married secondly to Damad Çerkes Mehmed Pasha;

|

|

|

|

Early life

Born in Manisa on 4 July 1546, Şehzade Murad was the oldest son of Sultan Selim II and his powerful wife Nurbanu Sultan. After his ceremonial circumcision in 1557, Murad was appointed sancakbeyi of Akşehir by Suleiman I (his grandfather) in 1558. At the age of 18 he was appointed sancakbeyi of Saruhan. Suleiman died when Murad was 20, and his father became the new sultan. Selim II broke with tradition by sending only his oldest son out of the palace to govern a province, and Murad was sent to Manisa.

A Fragment Of A Scroll, Depicting A Procession Of Sultan Murad IIi With Infantrymen Archers. |

📘 DETAILS & CATALOGUING

A fragment of a scroll, probably depicting a procession of Sultan Murad III with infantrymen & archers, Continental school, possibly Austrian, circa 1600 (L)

EXHIBITED

Couleurs d'Orient, Brussels 2010.

Turkophilia, Paris 2011.

LITERATURE

F. Hitzel et al. Couleurs d'Orient, Arts et arts de vivre dans l'Empire Ottoman, exhibition catalogue, Brussels 2010, p.13.

F. Hitzel et al. Turkophilia Revealed, exhibition catalogue, Paris 2011, p.81.

CATALOGUE NOTE

The present work depicts two classes of Janissary soldiers, respectively peyk bodyguardinfantrymen wielding their balta axes, and solak, denoting 'left-handed' in Turkish, wielding bows. Key components of the Sultan’s escort, it is likely the Sultan himself would have been represented on horseback to the right of the archers, who would commonly march beside their liege.

The fragment bears close similarity to manuscript albums of the late sixteenth century, commissioned by European courts from their ambassadors, notably those executed during the reign of Sultan Murad III (see, for example, those held in the Staats und Universitätsbibliothek, Bremen , the Codrington Library of All Souls College, Oxford, and particularly the Codex Vindobonensis 8626, Bartholomeus Pezzen's album, in which the placement of the peykler is particularly similar to the present work).

For a further example of the peyk bodyguards wielding balta in procession, see the exhibition catalogue War and Peace, Ottoman-Polish Relationships in the 15th-19th centuries (Kangal, Selmin, Turkish Republic Ministry of Culture, Istanbul 1999, pp.302, no.198 now in the Warsaw University Library T. 171, no.165). For a further illustration of traditional Janissary garb see Kangal, Selmin, for War and Peace, Ottoman-Polish Relationships in the 15th-19th centuries, Republic Ministry of Culture, Istanbul, 1999, pp.289-291, no.178-181.

|

|

|

|

|

Reign

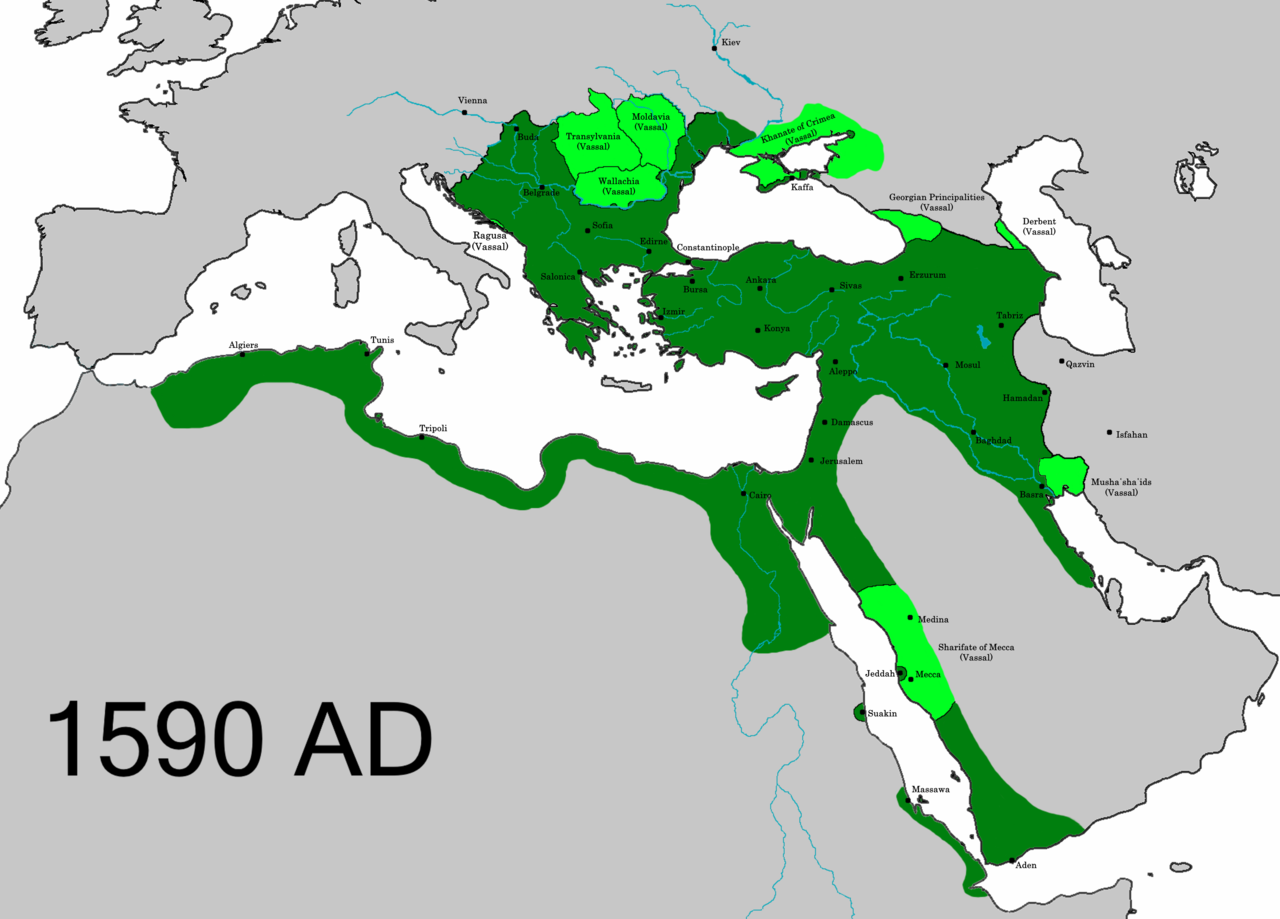

The Ottoman Empire reached its greatest extent in the Middle East under Murad III. |

|

Selim died in 1574 and was succeeded by Murad, who began his reign by having his five younger brothers strangled. His authority was undermined by harem influences – more specifically, those of his mother and later of his favorite wife Safiye Sultan, often to the detriment of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha’s influence on the court. Under Selim II power had only been maintained by the genius of the powerful Grand Vizier, Mehmed Sokollu, who remained in office until his assassination in October 1579. During Murad's reign the northern borders with the Habsburg Monarchy were defended by the Bosnian governor Hasan Predojević. The reign of Murad III was marked by exhausting wars on the empire’s western and eastern fronts. The Ottomans also suffered defeats in battles such as the Battle of Sisak.

The Ottomans had been at peace with the neighbouring rivaling Safavid Empire since 1555, per the Treaty of Amasya, that for some time had settled border disputes. But in 1577 Murad declared war, starting the Ottoman-Safavid War (1578-90), seeking to take advantage of the chaos in the Safavid court after the death of Shah Tahmasp I. Murad also tried to explore North America and make the ideas of colonizing America be more possible. However, he later abandoned all of these ideas after the Spanish navy responded by a naval attack on the Ottoman ships trying to explore North America. Murad was influenced by viziers Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha and Sinan Pasha and disregarded the opposing counsel of Grand Vizier Sokollu. Murad also fought the Safavids which would drag on for 12 years, ending with the Treaty of Constantinople (1590), which resulted in temporary significant territorial gains for the Ottomans.

Murad's reign was a time of financial stress for the Ottoman state. To keep up with changing military techniques, the Ottomans trained infantrymen in the use of firearms, paying them directly from the treasury. By 1580 an influx of silver from the New World had caused high inflation and social unrest, especially among Janissaries and government officials who were paid in debased currency. Deprivation from the resulting rebellions, coupled with the pressure of over-population, was especially felt in Anatolia. Competition for positions within the government grew fierce, leading to bribery and corruption. Ottoman and Habsburg sources accuse Murad himself of accepting enormous bribes, including 20,000 ducats from a statesman in exchange for the governorship of Tripoli and Tunisia, thus outbidding a rival who had tried bribing the Grand Vizier.

Numerous envoys and letters were exchanged between Elizabeth I and Sultan Murad III. In one correspondence, Murad entertained the notion that Islam and Protestantism had “much more in common than either did with Roman Catholicism, as both rejected the worship of idols,” and argued for an alliance between England and the Ottoman Empire. To the dismay of Catholic Europe, England exported tin and lead (for cannon-casting) and ammunition from the Ottoman Empire, and Elizabeth seriously discussed joint military operations with Murad III during the outbreak of war with Spain in 1585, as Francis Walsingham was lobbying for a direct Ottoman military involvement against the common Spanish enemy. This diplomacy would be continued under Murad's successor Mehmed III, by both the sultan and Safiye Sultan alike.

During his period, excessive inflation was experienced, the value of silver money was constantly played, food prices increased. 400 dirhams should be cut from 600 dirhams of silver, while 800 was cut, which meant 100 percent inflation. For the same reason, the purchasing power of wage earners has halved, and the inevitable consequence has been the uprising. |

Palace life

Following the example of his father Selim II, Murad was the second Ottoman sultan who never went on campaign during his reign, instead spending it entirely in Constantinople. During the final years of his reign, he did not even leave Topkapı Palace. For two consecutive years he did not attend the Friday procession to the imperial mosque — an unprecedented breaking of custom. The Ottoman historian Mustafa Selaniki wrote that whenever Murad planned to go out to Friday prayer, he changed his mind after hearing of alleged plots by the Janissaries to dethrone him once he left the palace. Murad withdrew from his subjects and spent the majority of his reign keeping to the company of few people and abiding by a daily routine structured by the five daily Islamic prayers. Murad's personal physician Domenico Hierosolimitano described a typical day in the life of the sultan:

“In the morning he rises at dawn to say his prayer for half an hour, then for another half hour he writes. Then he is given something pleasant as a collation, and afterwards sets himself to read for another hour. Then he begins to give audience to the members of the Divan on the four days of the week that this occurs, as had been said above. Then he goes for a walk through the garden, taking pleasure in the delight of fountains and animals for another hour, taking with him the dwarves, buffoons and others to entertain him. Then he goes back once again to studying until he considers the time for lunch has arrived. He stays at table only half an hour, and rises (to go) once again into the garden for as long as he pleases. Then he goes to say his midday prayer. Then he stops to pass the time and amuse himself with the women, and he will stay one or two hours with them, when it is time to say the evening prayer. Then he returns to his apartments or, if it pleases him more, he stays in the garden reading or passing the time until evening with the dwarfs and buffoons, and then he returns to say his prayers, that is at nightfall. Then he dines and takes more time over dinner than over lunch, making conversation until two hours after dark, until it is time for prayer [...] He never fails to observe this schedule every day.” ( Felek, Özgen. (2010). Re-creating image and identity: Dreams and visions as a means of Murad III's self-fashioning. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Michigan. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI. (Publication No. 3441203).)

Murad's sedentary lifestyle and lack of participation in military campaigns earned him the disapproval of Mustafa Âlî and Mustafa Selaniki, the major Ottoman historians who lived during his reign. Their negative portrayals of Murad influenced later historians. Both historians also accused Murad of sexual excess. Before becoming sultan, Murad had been loyal to Safiye Sultan, his Venetian-born concubine who had given him a son, Mehmed, and two daughters. His monogamy was disapproved of by his mother Nurbanu, who worried that Murad needed more sons to succeed him in case Mehmed died young. She also worried about Safiye's influence over her son and the Ottoman dynasty. Five or six years after his accession to the throne, Murad was given a pair of concubines by his sister Ismihan. Upon attempting sexual intercourse with them, he proved impotent. "The arrow [of Murad], [despite] keeping with his created nature, for many times [and] for many days has been unable to reach at the target of union and pleasure," wrote Mustafa Ali. Nurbanu accused Safiyye and her retainers of causing Murad's impotence with witchcraft. Several of Safiye's servants were tortured by eunuchs in order to discover a culprit. Court physicians, working under Nurbanu's orders, eventually prepared a successful cure, but a side effect was a drastic increase in sexual appetite — by the time Murad died, he was said to have fathered over a hundred children. Nineteen of these were executed by Mehmed III when he became sultan.

Influential ladies of his court included his mother Nurbanu Sultan, his sister Ismihan Sultan, wife of grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, and musahibes (favourites) mistress of the housekeeper Canfeda Hatun, mistress of financial affairs Raziye Hatun, and the poet Hubbi Hatun. |

Murad and the arts

Murad took great interest in the arts, particularly miniatures and books. He actively supported the court Society of Miniaturists, commissioning several volumes including the Siyer-i Nebi, the most heavily illustrated biographical work on the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Book of Skills, the Book of Festivities and the Book of Victories. He had two large alabaster urns transported from Pergamon and placed on two sides of the nave in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and a large wax candle dressed in tin which was donated by him to the Rila monastery in Bulgaria is on display in the monastery museum.

Murad also furnished the content of Kitabü’l-Menamat (The Book of Dreams), addressed to Murad's spiritual advisor, Şüca Dede. A collection of first person accounts, it tells of Murad’s spiritual experiences as a Sufi disciple. Compiled from thousands of letters Murad wrote describing his dream visions, it presents a hagiographic self-portrait. Murad dreams of various activities, including being stripped naked by his father and having to sit on his lap, single-handedly killing 12,000 infidels in battle, walking on water, ascending to heaven, and producing milk from his fingers. He frequently encounters the Prophet Muhammed, and in one dream sits in the Prophet's lap and kisses his mouth.

In another letter addressed to Şüca Dede, Murad wrote "I wish that God, may He be glorified and exalted, had not created this poor servant as the descendant of the Ottomans so that I would not hear this and that, and would not worry. I wish I were of unknown pedigree. Then, I would have one single task, and could ignore the whole world."

The diplomatic edition of these dream letters have been recently published by Ozgen Felek in Turkish. |

| |

Death

Murad died from what is assumed to be natural causes in the Topkapı Palace and was buried in tomb next to the Hagia Sophia. In the mausoleum are 54 sarcophagus of the sultan, his wives and children that are also buried there. He is also responsible for changing the burial customs of the sultans' mothers. Murad had his mother Nurbanu buried next to her husband Selim II, making her the first concubine to share a sultan's tomb. |

|

|

|

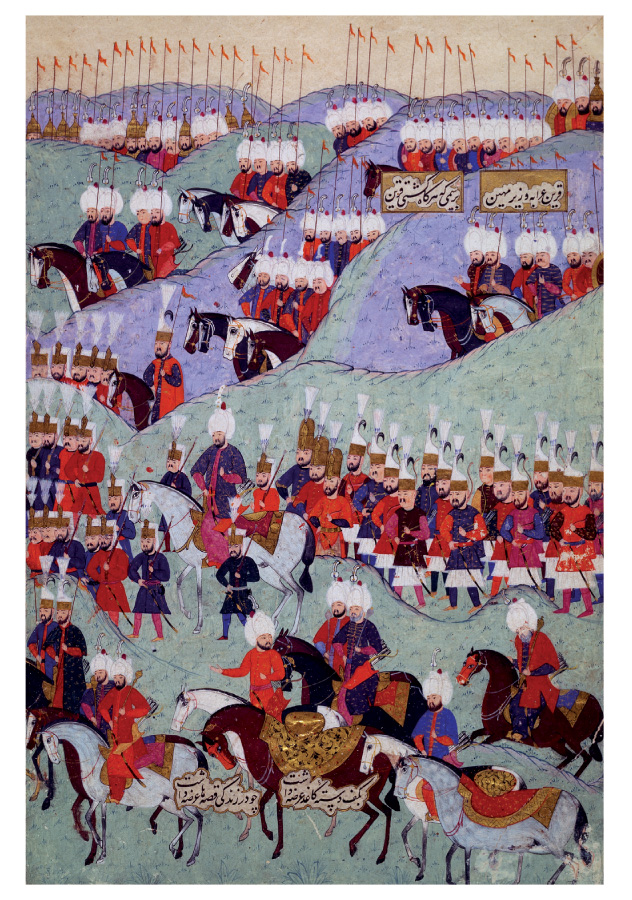

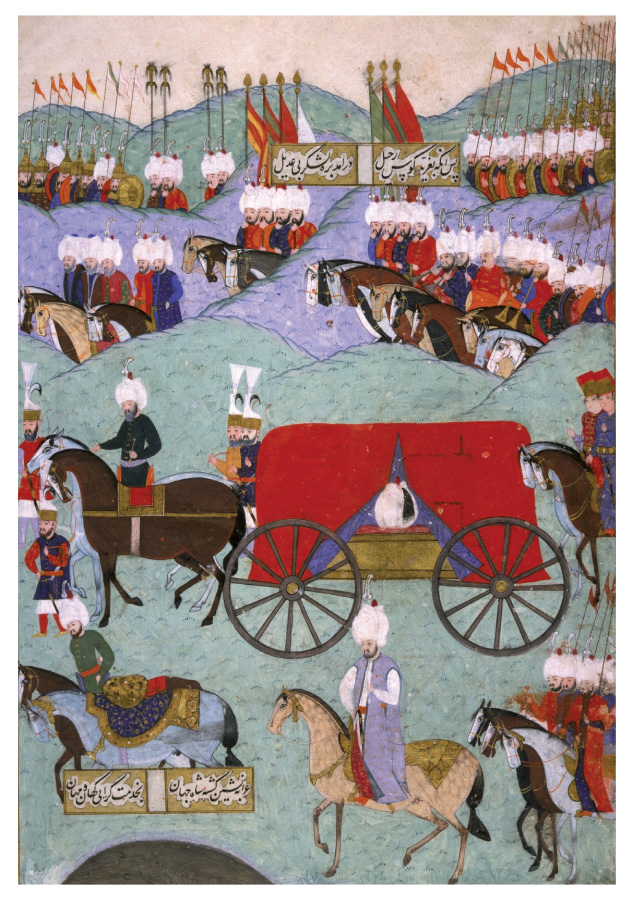

IMPERIAL PROCESSION

IMPERIAL PROCESSION (L)

This notecard folio presents the two halves of a double-page painting from a manuscript in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland, that was produced in 1579 for the Ottoman sultan Murad III (r. 1574-95). It is a history of Murad’s grandfather, Suleyman I. The Ottoman Empire was one of the greatest empires known to history. Ottoman rule began in Turkey in the late 13th century and extended until 1922, the year prior to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. Although there were many great Ottoman sultans, none was greater than Suleyman. Known in the West as the Magnificent and in the East as Qanuni, the Lawgiver, he ruled from 1520 to 1566, longer than any other Ottoman sultan. His vast empire included not only Turkey itself but lands stretching westwards through North Africa as far as Algeria, southwards to the Islamic Holy Places of Mecca and Medina, and northwards into Europe to include most of Hungary. He died in 1566, while on campaign and the night before an Ottoman victory over the Hungarian army at the Battle of Szigetvár.

The double-page painting reproduced on these cards depicts the return of the sultan’s body to Istanbul following his death at Szigetvár, Hungary. In the left half of the painting, some soldiers walk, others are mounted as they accompany their beloved sultan home one last time. The artist’s dense arrangement of serried rows of figures emerging from behind the hills creates the impression of an army of immense size — a never-ending wave of grieving figures overwhelming the countryside they pass through. In the right half of the painting, a carriage carries the body of the deceased sultan, and through the open curtain his turban, set carefully on the coffin, can be glimpsed. Throughout the composition, the artist has used a striking palette of mainly red, blue, and pale green, all offset by the dazzling white of the figures’ turbans and the dark tones of the horses. |

| |

Imperial Procession Notecard Folio; Published with Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland. |

|

Imperial Procession Notecard Folio; Published with Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland. |

|

|

|

|

|

Surname-i Hümayun (‘Book of the Imperial Circumcision Festival’)

Surname-i Hümayun (‘Book of the Imperial Circumcision Festival’) (W)

Name of Object:

Surname-i Hümayun (‘Book of the Imperial Circumcision Festival’)

Location:

Sultanahmet, Istanbul, Turkey

Holding Museum:

Topkapı Palace Museum

Date of Object:

Hegira 991–7 / AD 1583–8

Artist(s) / Craftsperson(s):

In the Surname, the writer Intizami describes the preparation of the work in a section entitled ‘Description of the painter and his qualities’, stating that it was prepared by Naqqash Osman (who, like himself, was from the town of Foça in Herzegovina) and his team, although he does not give the names of the members of the team. A document dated 997 (AD 1588) written by the court panegyrist Sayyid Loqman on the subject of raising the salaries of the team working on the Hünername and the Surname, though, does list the names of the team members. Although it is impossible to determine from this document who was working on the Hünername and who on the Surname (or on both), the document is important because it gives a general idea of which painters (naqqash in Turkish) and other artists might have been working on Naqqash Osman’s team. The names that appear in this document are:

Calligraphers: Seyyid Kasım; Mustafa; Feramruz?; Ali; Abdurrahman.

Bookbinders: Abdi Şaban; Mehmet Haydar; Kara Mehmed; Mehmed …; Recep Abdullah.

Painters (naqqash): Osman; Lütfi; Ali; Mehmed Haydar; Velican; Mehmed Musavvir; Molla … ; İbrahim; [another] Osman; Ahmed Abdullah; Hüseyin Zergub; Mahmud Müzehib?; … Abdullah …

Illuminators: Musa Ahmed; Yahya; Seydi; Abdi Zergub; Şaban; Hızır Gazi; Mehmed Abdullah; Mehmed Mustafa; Nasuh bin Abdullah; Perviz Abdullah; Abd … Yakub; Davud Abdullah; Yusuf Abdullah.

Museum Inventory Number:

H. 1344

Material(s) / Technique(s):

Finished (aharlı) paper, ink, watercolour, gilding, leather (binding).

Dimensions:

Height 33.5 cm, width 23.5 cm

Period / Dynasty:

Ottoman

Provenance:

Istanbul, Turkey.

Description:

The Surname-i Hümayun ('Book of the Imperial Circumcision Festival') is a work dealing with the celebrations held for the circumcision festival of Prince Mehmed, son of Sultan Murad III, which lasted for 52 days and 52 nights in AH 990 / AD 1582. It documents, in both word and image, how during the festivities the craft guilds paraded their various products, how a variety of entertainments were organised, how banquets were held and food distributed to the public every day, how the sultan would scatter gold and silver among the people from time to time, how poor children were circumcised and given new clothes, how beggars were made happy, and how people who had been imprisoned for debt were granted their freedom by having their debts paid. For this reason the Surname is an important historical source providing for us a record of the AH 10th- / AD 16th-century Ottoman lifestyle; its economy, social life, culture, art and entertainment.

The celebration was held in the Hippodrome, i.e. the 'Horse Square'. The Ibrahim Pasha Palace is depicted here, and the three-storey wooden spectators' gallery erected at one of its corners for the use of palace officials and representatives of foreign governments, is an indispensable element of the scenes in the Surname.

One of these scenes represents the parade of the glassmakers' guild. Here the sultan, seated on the enclosed balcony of the audience hall in the Ibrahim Pasha Palace, watches the glassmakers' guild along with the assembled people and the guests sitting in the spectators' gallery. The glassmakers present the glass objects they have made, even showing the stages of glass production and the tools they use with the help of a furnace mounted on a wheeled wagon.

Another painting in the Surname shows the procession of architects and engineers with a faithful replica of the Süleymaniye Mosque made of wood and ivory. This picture is noteworthy because it represents Ottoman art in all its splendour, celebrated in both the depiction of the architect Sinan, who was still alive in this period and probably participated in this parade, and, through his most monumental building: the Süleymaniye Mosque.

The celebrations of the circumcision festival are transformed into a painted story through 250 double-page miniatures with compositions generally similar to the two seen here.

View Short Description

Original Owner:

Sultan Murad III (r. AH 982-1003 / AD 1574-95)

How date and origin were established:

Since some pages of the manuscript are missing, including the colophon, it has been ascertained from the Kepeci Ruus register in the archives (3 Safar 997/1583 no. 250, 37) that it was completed in 997 / 1588.

How Object was obtained:

The Surname was made for Sultan Murad III in the Topkapi Palace atelier and is still in the palace library.

How provenance was established:

It is known that this manuscript was prepared by the team of artists in the Topkapi Palace atelier, and that it was therefore produced in Istanbul.

Selected bibliography:

And, M., Kırk Gün Kırk Gece, Istanbul, 1959.

Atasoy, N., Surname-i Hümayun, Istanbul, 1998.

Atasoy, N., “Tarih Konulu Minyatürlerin Usta Nakkaşı Osman”, Sanat Dünyamız, 73 (1999), pp.213–21.

İpşiroğlu, M.Ş. “Das Hochzeitbuch Murats III”, Deutsch-Türkische Gesellschaft, Bonn, 1960.

Tansuğ, S. Şenlikname Düzeni, Istanbul, 1961.

Citation of this web page:

Şebnem Tamcan "Surname-i Hümayun (‘Book of the Imperial Circumcision Festival’)" in Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2020. http://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;tr;Mus01_A;49;en

Prepared by: Şebnem Tamcan

Şebnem Tamcan is a research assistant at the Department of Art History of the Faculty of Letters, Ege University, Izmir. She was born in Izmir, Turkey, in 1978. She graduated from the Department of Art History, Ege University, in 2000. She completed her Master's in 2005 with a thesis entitled “The Depictions in the Zigetvar Campaign History Manuscript H.1339 at Topkapı Palace Museum Library”.

Translation by: Barry Wood

Barry Wood is Curator (Islamic Gallery Project) in the Asian Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. He studied history of art at Johns Hopkins University and history of Islamic art and architecture at Harvard University, from where he obtained his Ph.D. in 2002. He has taught at Harvard, Eastern Mediterranean University, the School of Oriental and African Studies, and the Courtauld Institute of Art. He has also worked at the Harvard University Art Museums and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. He has published on topics ranging from Persian manuscripts to the history of exhibitions., İnci Türkoğlu

İnci Türkoğlu has been working as a tourist guide and freelance consultant in tourism and publishing since 1993. She was born in Alaşehir, Turkey, in 1967. She graduated from the English Department of Bornova Anatolian High School in 1985 and lived in the USA for a year as an exchange student. She graduated from the Department of Electronic Engineering of the Faculty of Architecture and Engineering, Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir, and the professional tourist guide courses of the Ministry of Tourism in 1991. She worked as an engineer for a while. She graduated from the Department of Art History, Faculty of Letters, Ege University, Izmir, in 1997 with an undergraduate thesis entitled “Byzantine House Architecture in Western Anatolia”. She completed her Master's at the Byzantine Art branch of the same department in 2001 with a thesis entitled “Synagogue Architecture in Turkey from Antiquity to the Present”. She has published on art history and tourism.

Translation copyedited by: Mandi Gomez.

MWNF Working Number: TR 79

Source: [http://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;tr;Mus01_A;49;en&cp] |

|

|

|

|

|

|